ADVERTISEMENT:

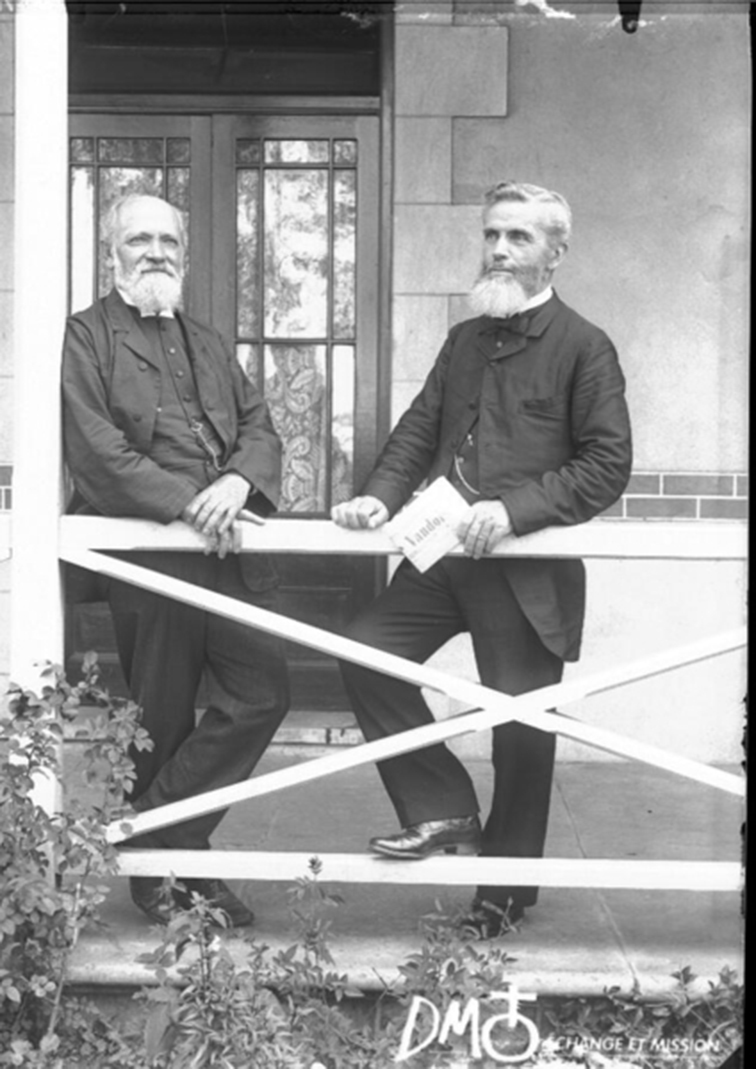

Charles Leach, the well-known historian, standing next to the Cuénod graves at the Valdezia cemetery.

A hunt for Swiss missionaries' graves reveals more than just pictures

Date: 16 December 2023 By: Anton van Zyl

A short email received two weeks ago prompted the search for graves. Perhaps the relatively slow weekend, with little happening, contributed to the decision to explore the final resting place of two missionaries, René Cuénod and his wife, Marguerite.

“My grandfather was a Swiss missionary who worked in the area of Louis Trichardt, the Swiss mission hospital, Lemana, and Valdezia,” wrote Michael A. Cuénod. He explained that his grandfather had died around late 1980 and was buried alongside his wife in the cemetery at Valdezia. “Do you know anyone from the area or a contact I could liaise with to get more information, please?” he asked.

Well, of course, we know someone. Who better to ask than local historian, model builder, car restorer, tour guide, and often described as a living library, Mr Charles Leach, who incidentally does not stay far from Valdezia? Convincing him did not take much, and on Saturday afternoon, we set off to the small graveyard near the historic church at Valdezia.

Today, Valdezia resembles a rural village, much like dozens of others in the proximity of Elim, with a population of between 13,000 and 15,000 people, and many working on the farms surrounding the village. But Valdezia used to have a unique character – as the birthplace of the Swiss Mission in the northern part of the country.

|

|

|

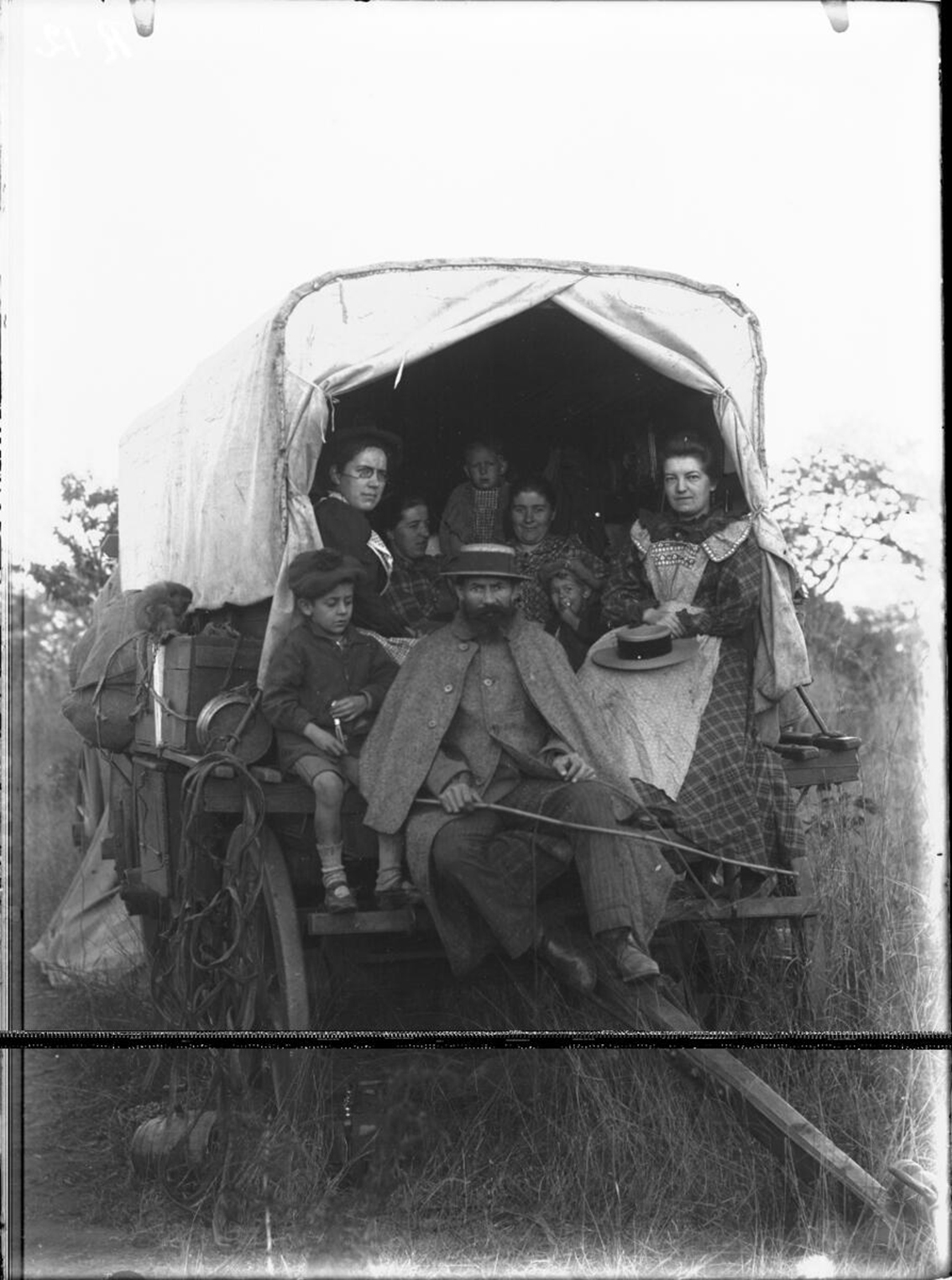

The two Swiss missionaries, Ernest Creux and Paul Berthoud, photographed in Pretoria around 1896. Source: USC Libraries. |

When Rev Ernest Creux and his colleague, Rev Paul Berthoud, arrived in the region known as the Spelonken, they quickly realised that their task would not be easy. On 9 July 1875, their wagons - with their wives and children - stopped at the farm Klipfontein, not far from where João Albasini lived and traded. They bought the farm from a Scottish trader, Mr John Watt, but only a few rustic huts and a small, tin-roofed building had been erected. They called it Valdezia, after their home canton (province), Vaud.

The language barrier was initially a major stumbling block. Both missionaries could speak some Sotho, but they quickly realised that the local people spoke Shigwamba or Tsonga. What counted in their favour was that two Evangelists, Eliakim Matlanyane and Asser Segagabane, had arrived at Klipfontein two years earlier, in 1873, to start missionary work. This made gaining the trust of the local people much easier.

Tragedy struck very early, and the first of what would become many graves had to be dug. In 1879 and 1880, malaria claimed the lives of Mrs Berthoud and, one by one, all five of her children. Rev Creux’s family was also not spared, and three of his children died of diphtheria.

|

|

|

Photograph of Henri Berthoud, his wife and their children |

After the death of his wife and children, Paul Berthoud returned to Switzerland, but he was replaced by his younger brother, Henri. Whereas, before, the missionaries battled to master the “Gwamba” language and often preached in Sesotho, Henri Berthoud felt he had to master the language to spread the Gospel. In June 1882, he spearheaded the project to translate part of the Old Testament into Shigwamba.

By April 1883, Berthoud was teaching the Ten Commandments in Shigwamba rather than Sesotho and had compiled a rudimentary grammar and vocabulary guide. In Switzerland, his brother Paul oversaw the production of the first book in Shigwamba, a Bible reader, and a collection of hymns that became known locally as the “buku”.

Rev Paul Berthoud returned to Africa to establish a mission station and a training institution at Rikatla in Mozambique and in 1889 another station at Lourenço Marques (Maputo). Though he retired in 1903, he returned in 1906 to Mozambique, where he eventually died.

At Valdezia, his brother Henri continued to help structure and develop the local language, which he later described as Tonga, or what we today know as Xitsonga.

The role that the Berthoud brothers and the various Swiss missionaries played in the full translation of the Xitsonga Bible and formalising the language can fill many chapters. Still, seeing that we need to get to the hunt for the Cuénod graves, we will have to move on.

|

|

|

Rev Paul Rosset, his wife and his children on a journey in Mhinga. |

Henri Berthoud and his wife, Emmy, had three daughters, Marguerite, Emmeline, and Ninette, and one son, Francis. Marguerite, the eldest daughter, was born on 19 December 1885. When her father died on 31 December 1904 (aged 49), she returned to Switzerland with her mother and siblings. Like all missionary families, they must have been quite active in church activities, and this was probably where she met René Cuénod.

His father, Edouard Cuénod, was a civil engineer and his company specialised in building railway lines, railway tunnels and major highways. At the time, René’s father was building the railway line up the Salève mountain just above Geneva.

René grew up in Geneva and studied to become a minister. The push to become a missionary seemed to have been quite important in French-speaking Switzerland at the time. Marguerite, who was fluent in Tsonga, taught her husband the language while they were in Switzerland. When the couple returned to South Africa in 1914, he was confident enough in his abilities that his first sermon at Valdezia was delivered in Tsonga.

|

|

|

A photo of the Cuénod family taken in Switzerland, before the birth of Claude (who was born in 1924). At the back on the left is René Cuénod with his wife, Marguerite on the right. Between them is the eldest daughter, Jacqueline. Valentine sits on the right, with Pierre Henri siting on his father's lap. The toddler in front is Jean-René. |

The Cuénod couple played an important role in the full translation of the Bible into Xitsonga. This process, however, started more than two decades before René Cuénod arrived in the country.

In 1892, the Gospel according to Luke and the Book of Acts were translated. Paul Berthoud and Ernest Creux were very involved with this project, assisted by Timothy Mandlati and Calvin Maphophe. The first New Testament in Xitsonga was translated and printed in 1894, and here the names of Henri Berthoud, Auguste Jaques, and Eugène Thomas appear along with the previous translators. The first Xitsonga Bible appeared in 1907, and it was printed by Georges Bridel in Lausanne.

This version was fully revised in 1929, but this time the work was credited to Marguerite Cuénod, René Cuénod, Joseph Mawelele, and Edward Mthebule. Much of the work must probably be credited to René Cuénod, who was quite a linguist, like his father-in-law, Henri Berthoud.

The Cuénod couple had five children, the eldest being Jacqueline, born in 1915. She lived to the ripe age of 90 and died in February 2006 in Randburg. In 1916, Valentine Cuénod was born, but she died at sea in 1966, apparently from a heart attack. The third-born was Pierre Henri Cuénod, who stayed in Elim until his death in July 2000, aged 82.

|

|

A painting of the missionary house at Valdezia. Photo: Yvonne Cuénod. |

Pierre Henri was born in Middelburg (Mpumalanga). After finishing school, he studied Bantu Law & Administration at the University of Cape Town. He went to Sedara, in Natal, where he studied agriculture before moving back to the Soutpansberg where he farmed in the Bandelierkop area. In 1966, when Philippe de Montmollin died, the Swiss Mission asked him to replace Philippe as manager of the three Mission farms, Elim, Valdezia and Kuruleni. He worked for the Mission until 1980.

Pierre and his wife, Françoise Suzanne, had four daughters. Yvonne, who contributed much of the information used in this article, was the eldest.

René and Marguerite Cuénod’s fourth child was Jean-René Cuénod, born on 23 September 1920. He died during the Second World War, in 1941, while serving in Sidi-Redzegh, Libya. He was one of 24 residents of the Soutpansberg district who died in this war.

The last-born son, Claude Arnold Cuénod, was also the father of Michael Cuénod (the relative who inquired about the graves). He was born on 20 May 1924 in the Swiss embassy in what is now Maputo. He and his wife had a daughter and four sons. Michael was the youngest child. Claude Cuénod died on 16 April 1981 in Harare, only a few months after his dad had passed away.

However, since the article concerns the search for the Cuénod graves, we need to return to the little graveyard at Valdezia.

To find the graveyard is not difficult. Even Google Maps has it listed and will lead the explorer past the Mambedi orchards and into Valdezia. Before you reach the graveyard, you pass the historic church building of the Evangelical Presbyterian Church in South Africa (EPCSA). Sadly, the building is fenced off with a concrete palisade.

The graveyard is a mixture of simplicity and extravagance. Whereas the older graves have very plain headstones, the newer graves are large granite constructions, often fenced off to keep vandals at bay. Among the older graves, surnames of legendary evangelists such as Marivate and even Baloyi are common. Five graves, seemingly those of the Swiss missionaries, are grouped. The oldest of these is that of Paul Rosset (1866-1930). Next to him lies his wife, with the inscription on the headstone stating: “Yefro E. Rosset. 1868 – 1950”.

Reverend Paul Rosset and Emilie Rosset-Audemar arrived in the Soutpansberg on 4 May 1892. One of their first tasks was to establish a new missionary station at Crook’s Corner, in the northeastern corner of the country, for the people of the Maluleke clan. Their plans were thwarted when rinderpest swept through the country in 1896, killing all cattle, including the oxen. This was accompanied by a severe drought and subsequent famine. The Rosset family was forced to abandon their plan and walk back to Elim, a distance of more than 200 km.

But Paul and Emile Rosset left behind another huge contribution to the people of the region, in the form of their son, Jean-Alfred Rosset. He and his wife Dr Odette Rosset-Berdez started working at Elim Hospital. Dr PH Jaques, who took over duties from Dr Rosset in 1967, had this to say about his predecessor: “He was a magnificent surgeon with incredible versatility. He was able to do the most intricate operations using the simplest of instruments. His fame as a surgeon and doctor resulted in many patients from as far afield as Natal, the Cape, and the Witwatersrand travelling to Elim to see him, even many years after he had left. He died while on holiday in Europe in 1972.” (PH Jaques unpublished data, 1999).

Long-time residents of the Soutpansberg will know the name Denise Milton, wife of well-known farmer Rob Milton. Denise is the daughter of Jean-Alfred and Odette Rosset.

In the Valdezia graveyard, next to the Rosset graves, are the graves of René and Marguerite Cuénod. The headstones are similar, with just the names, date of birth, and date of death inscribed. Marguerite died on 13 February 1966, when she was 79 years old. Her husband died on 28 October 1980, only a few weeks before his 92nd birthday.

The search for the grave of Henri Berthoud was fruitless. Yvonne Cuénod shed some light on this mystery when she was later contacted. “Henri Berthoud’s grave, as far as I can remember, was near the house that is now a clinic. If you stand facing the Soutpansberg, slightly to the right, you may find the graves outside the clinic fence. Paul Berthoud’s daughter, Ruth, was also buried there,” she wrote.

Perhaps that will be a search for another day.

(Thanks to Michael and Yvonne Cuénod for providing information that could be used for this article. The remainder of the information was collected from a vast library of research documents on the Swiss Missionary’s activities in South Africa.)

Viewed: 3635

|

|

Tweet |

-

Ben se skielike dood kom as groot skok

26 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Rotariërs maak bittersoet laaste skenking aan Bergcare

26 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Raliphada finally gets appointed as CFO of Makhado

26 July 2024 By Kaizer Nengovhela -

RAL says work did not stop on busy R522 road

26 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Koben droom steeds groot

26 July 2024 By Karla van Zyl

Anton van Zyl

Anton van Zyl has been with the Zoutpansberger and Limpopo Mirror since 1990. He graduated from the Rand Afrikaans University (now University of Johannesburg) and obtained a BA Communications degree. He is a founder member of the Association of Independent Publishers.

More photos...

ADVERTISEMENT

-

MMSEZ pushes for township development

12 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Sheryl chosen again to represent Team SA at Paris Paralympics

12 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Is Musina a gravy train for officials and councillors?

19 July 2024 By Anton van Zyl -

'Waterless' Vhembe causes problems for Phelophepa Health Train

27 June 2024 By Thembi Siaga -

Fuel company remains closed after SARS raid

18 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT:

ADVERTISEMENT