ADVERTISEMENT:

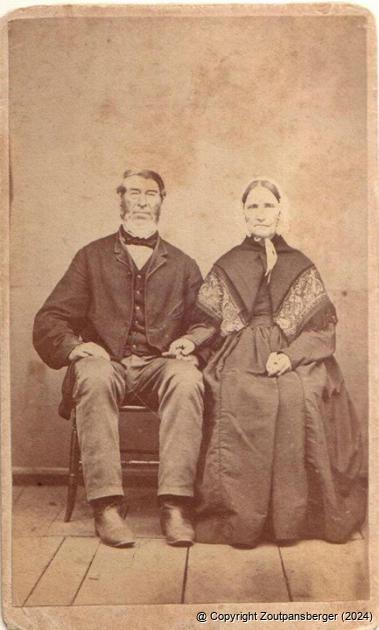

The photo of Andries Hendrik Potgieter and his wife.Could this photo possibly have been taken before his death in December 1852?

Did an early photographer capture Boer leader's “likeness”?

Date: 11 February 2019 By: Anton van Zyl

In last week’s edition, we set the stage for a “history mystery”. We introduced a photo proclaimed to be that of the Voortrekker leader, Andries Hendrik Potgieter, and started questioning its authenticity. Potgieter died in December 1852, but we mentioned that the first reports of photography in South Africa date back to 1846. It could possibly be a genuine photo, but it could also be that the photograph so commonly used next to articles about the Boer commandant is a fake.

Last week, we focused on the life of Potgieter, starting with his birth in the Graaff Reinett district in the Cape Colony on 19 December 1792 and ending with his death in Zoutpansbergdorp (later Schoemansdal), on 16 December 1852. We also speculated as to which of his four (or five) wives could be sitting next to him in the photograph.

In this week’s article, we approach the “investigation” from a different angle. We look at the birth of photography, when it probably arrived on southern African shores and what the likelihood is that Potgieter would have been in close proximity of a photographic studio.

The roots of photography

Although the “camera obscura” existed for thousands of years, this was mostly a device used to deflect light and project an image onto a surface. Most historians give credit to the Frenchman, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765 – 1833) for first succeeding in “capturing” such an image. In the early 1820s, Niépce used a pewter plate coated with light-sensitive asphalt compound suspended in oil of lavender to capture an image. It took him eight hours to reproduce a rather dull-looking reflection of the area outside his second-storey apartment.

The man who probably had the biggest influence on early photography (and also important for our story), is Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787 – 1851). In 1835, Daguerre exposed a plate coated with light-sensitive silver iodide, which he in turn exposed to mercury vapor. It took Daguerre a few more years to sort out all the nitty gritty, but in August 1839 the French Academy of Art and Sciences heard the exciting news of an invention that would capture more than the imagination of the world.

The daguerreotypes, as the new shiny “likenesses” quickly became known, were an immediate hit. A daguerreotype “capturing” apparatus was developed by Alphons Giroux in 1839 and became the first camera manufactured in quantities. Suddenly more and more people could experiment with these new “magic” boxes and produce images of exceptional quality. All you needed was Mr Giroux’s apparatus, very shiny polished copper plates, chemicals such as silver iodide and mercury vapour, sensitizing and developing boxes, and an overabundant amount of patience and stubbornness.

Over the next few years, several other manufacturers started to put their daguerreotype cameras on the market and in all the squares of Paris the three-legged dark boxes were planted in front of churches and palaces. The “daguerreotypists” were sent in all directions, also to Africa, where late in 1839 several groups tried to capture images of Egypt’s treasures such as the Sphinx and the pyramids. In Britain, 51 photographers were counted during the census of 1851. The bulk of the photographers, however, operated from France.

An African invasion

As expected, it did not take long for photography to reach the shores of southern Africa. The first name mentioned is that of British photographer Charles Shepherd. He is recorded to have travelled to Calcutta in India in 1840 to take photos there. He must have passed the Cape of Good Hope on the way and stepped ashore. A year later, a French naval captain, Augustin Lucas, took the first photos in Sydney, Australia. He also had to travel past the Cape to reach the land down under and very possibly spent some time on African shores. They must have disembarked at either Table Bay or Algoa Bay (Port Elizabeth).

In 1845, French photographer E Thiésson visited Sofala (Mozambique) and took photos of the native people. In his excellent book Silver Images, published in 1958, Dr AD Bensusan speculates that this could have been the famous Native Queen Xai Xai in the province of Zavala. He reckoned that the subject must have been an important dignitary, considering the cost of the process and the effort involved.

The first real evidence of a photographer in action in South Africa is found in October 1846. A French photographer, Monsieur MJ Léger, was someone who loved travel and adventure. On his return from India he disembarked at Port Elizabeth, where he met William Ring, a local bookseller, stationer and tobacconist. Mr Ring also had a circulating library and newsroom in the town, which Léger used to set up his apparatus. He advertised that he would take likenesses by the photographic process at £1,10.

It seemed that Léger enjoyed his stay in Port Elizabeth so much that he decided to hang around a bit longer. Ring also realised that money could be made with this new invention and he and Léger teamed up. Their first venture took them to Grahamstown, where they opened a studio. In November 1846, they held a photographic art exhibition in the small town where the daguerreotypes were displayed. This, in all probability, was the first photographic exhibition ever held in Africa.

In 1847, four Daguerreotypists could already be found in Cape Town. Professor A Boisse (from Paris) had a studio in Longmarket Street, while Carel Sparmann, his assistant E Jones and Dr SNH von Sweel also offered to take portraits “in all sorts of weather”. A year later, William Waller started taking daguerreotypes from premises at 4 Church Street, Cape Town, and a vague reference is made to a photographer in Simon’s Town.

As far as the rest of southern Africa was concerned, references to a Durban-based dispensing chemist, WH Burgess, who advertised that he could take likenesses in 1857, can be found. A furniture dealer in Graaff-Reinet, James Hensley, took portraits in 1852, using the daguerreotype process. Some photographers could quite possibly have been in the then Delagoa Bay in the 1850s, but no records are available.

Keeping up with technology

We need to pause a bit and look at the processes used by early photographers. Up to the mid-1850s, the scene was dominated by the daguerreotype process. Daguerreotypes were easily identifiable, because they were shiny and had to be viewed at an almost 45-degree angle. Some of the sizes were as small as shirt buttons. The last successful daguerreotypist to reach Cape Town was probably John Paul in February 1851. He introduced daguerreotypes up to 8 inches (just over 20cm).

An English scientist and inventor, William Henry Fox Talbot, introduced the calotype process in 1841. This technique makes use of a sheet of paper coated with silver chloride. When the sheet is exposed to light in a camera obscura, those areas hit by light become dark in tone, yielding a negative image. One of the big advantages of the calotype process is that it allows the photographer to make an unlimited number of copies, using a simple salted paper process to make contact prints. This was not possible with daguerreotypes.

The setback for this type of photography was that Talbot had strict patent rights and it was fairly expensive. The earliest record of this type of photography being used in South Africa dates back to 1854, when Oliver Lester used it at his Jetty Street studio in Port Elizabeth.

The year 1851 saw another Eureka moment for the photographic industry when Frederick Scott Archer introduced his wet-plate collodion process. For the next almost 50 years, this process became a popular choice for professional and amateur photographers. The process was a lot less expensive than the daguerreotype and more immediate, with exceptional detail and contrast.

Space unfortunately does not allow a detailed description of how the wet-plate collodion process works. It was described as a “wet” process, because from the time when the collodion was poured onto the plate (glass or metal), the photographer only had about 10 to 15 minutes to take the picture, develop the image and then “fix” it with chemicals such as potassium cyanide. It was a process that required a lot of skill and experience.

For our story, however, we need to move on, as Hendrik Potgieter died in 1852 and the first records of wet-plate collodion being used in South Africa dates back to 1854 when a Cape Town-based photographer, William Syme, advertised that he was prepared to take photographs using the collodion process.

The last process used by photographers in the mid-1800s that is important for our story is the carte de visite. This format was patented by the French photographer Andre Adolphe Eugene Disdéri (1819–1889) in 1854. In short, it entails an albumen print mounted on a piece of card the size of a formal visiting card—hence the name. In South Africa it became popular in the 1860s. It is recognisable by the smaller size (normally 4x3 inches, or 10cm x 7,6cm), printed on cardboard.

Why is this important?

We have reached the end of the second article, but we need to summarize what we have found and what we are looking for.

Firstly, we know that the photo of Potgieter must have been taken between about November 1846 and December 1852. We also know that it must have been taken by a daguerreotypist, since the other processes were either introduced after Potgieter’s death or were not available here.

In next week’s final chapter, we need to look at the movements of the commandant. Was he close to Cape Town or Port Elizabeth during the last few years of his life? Was the photo perhaps taken when he visited Mozambique?

Scrutinizing the photo to see what process was used is also important. Could it perhaps be a copy of an original daguerreotype?

To be continued …

(Most of the information used in this article comes from the book, Silver Images, by Dr AD Bensusan, published in 1966 by Howard Timmins.

Viewed: 2034

|

|

Tweet |

-

Ben se skielike dood kom as groot skok

26 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Rotariërs maak bittersoet laaste skenking aan Bergcare

26 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Raliphada finally gets appointed as CFO of Makhado

26 July 2024 By Kaizer Nengovhela -

RAL says work did not stop on busy R522 road

26 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Koben droom steeds groot

26 July 2024 By Karla van Zyl

Anton van Zyl

Anton van Zyl has been with the Zoutpansberger and Limpopo Mirror since 1990. He graduated from the Rand Afrikaans University (now University of Johannesburg) and obtained a BA Communications degree. He is a founder member of the Association of Independent Publishers.

More photos...

E Thiésson visited Sofala (Mozambique) in 1845 and took photos of the native people. This may be the famous Native Queen Xai Xai in the province of Zavala. (Source: Silver Images by Dr AD Bensusan)

The earliest surviving camera used in Africa. It was brought to South Africa in 1856 by Otto Mehliss, a German settler. (Source: Silver Images by Dr AD Bensusan)

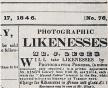

An advertisement that appeared in the Eastern Province Herald on 17 October 1846. (Source: Silver Images by Dr AD Bensusan)

ADVERTISEMENT

-

MMSEZ pushes for township development

12 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Sheryl chosen again to represent Team SA at Paris Paralympics

12 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Is Musina a gravy train for officials and councillors?

19 July 2024 By Anton van Zyl -

'Waterless' Vhembe causes problems for Phelophepa Health Train

27 June 2024 By Thembi Siaga -

Fuel company remains closed after SARS raid

18 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT:

ADVERTISEMENT