ADVERTISEMENT:

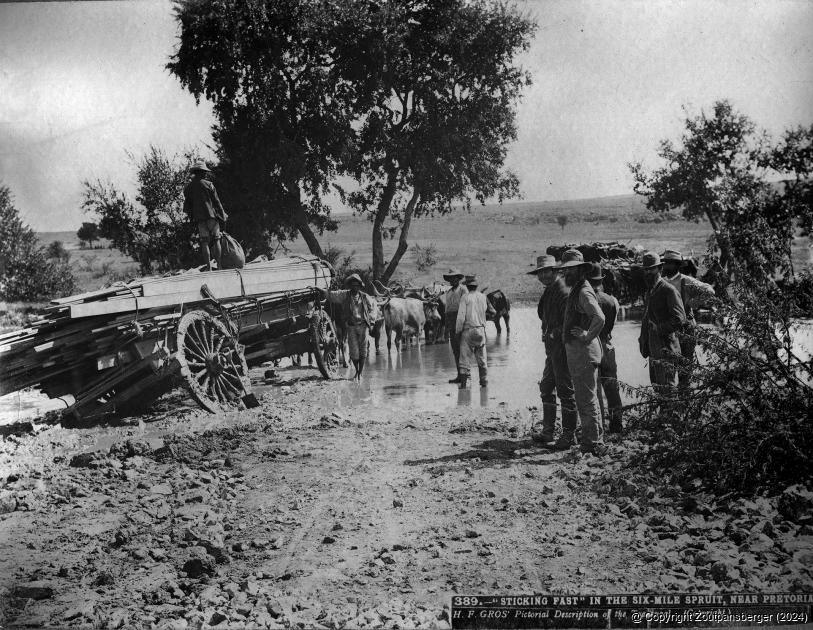

A historic photo taken by HF Gros in the late 1800s shows an ox wagon getting stuck in the mud near Pretoria. The Chambers family would have travelled in a similar waggon.

The amazing story of Dina Fourie

Date: 26 August 2017 By: Anton van Zyl

A year or so ago, I visited the graveyard at Schoemansdal, some 16 kilometres west of Louis Trichardt. This is, of course, the town that was abandoned in 1867, following a series of guerrilla attacks by Makhado and, more specifically, Katze-Katze. Many years later, the graveyard was restored with a memorial stone being erected for General AH Potgieter, who died there. The names of the other people in the graveyard who could be identified are also inscribed on a granite stone. These names make for interesting reading.

Apart from the Potgieters, Bothas and the Schoemans, there are several surnames that have no Dutch origin, such as Augusto Crevallio, the Portuguese shop owner, the Kelly family (Scottish), a person called Horney (described as a sailor) and Glynn, referred to as an English carpenter. At the very end of the list is a name “Baby Chambers” and in brackets it is said that she was three weeks old when she died. This week’s story is about her rather remarkable mother, Dina Fourie.

The story of Dina Fourie has been told on a couple occasions throughout the years. One of the Soutpansberg’s better-known authors, Dorothea Möller-Malan, wrote a book about her, but more recently a Hoedspruit historian, Herman Labuschagne, captured her amazing story in an article. We had to shorten it slightly, but here it is:

By Herman Labuschagne

A dear friend of mine asked me to share the story below, seeing that this is Women's Month in South Africa. I wrote this story in the Lowveld, back in 2001, because I found it both one of the saddest and one of the most inspiring tales I’ve ever known.

Whenever life deals me with a brutal hand, I often think of Dina Fourie, and then I am reminded that no matter how bad things are, a young woman once endured incomparably worse and never broke, nor lost her smile. If she could deal with it, then so can I.

This is a long story, friends, and you will not believe the amount of sadness that it contains. Yet, it has a small, but happy ending. I hope it will inspire you, as it continues to inspire me after all these years.

“There is always something new from Africa” — Ancient Roman Saying

Having a very active interest in military history, I have always been struck by how the brunt of most wars and times of terrible suffering often ultimately seem to fall on women.

One often reads about the magnificent exploits of brave warriors and daring fighters, but most of the time, the brave tales of the women who have stood behind such men have been forgotten by history. Over the years, I have come to see that there have been women whose bravery and sheer will to survive should stand as a finger of encouragement to all of us. Not only in times of war, but also in times of great disaster.

Up north, in the city of Polokwane, lies the grave of such a woman. Today, very few people – almost nobody – will be able to tell you who Dina Fourie was. For a long time I have thought it a shame that her story has been told so seldom, and whenever I see life hurtling down the fast track of disaster, it is Dina Fourie that I think about. The woman who did not know the meaning of “giving up.”

Dina Fourie must have been a remarkable woman by any standard you would care to mention. Her life had been plagued by misfortune almost from beginning to end, yet she never could give up on her will to survive and continue life where it had seemingly ended her entire world. No photographs of Dina Fourie exist today, but those who knew her said that she had been a little plump, with fair hair and with a most striking set of eyes, as blue as the sky. It was also said that, if ever there had been a person with a heart of gold, that person was Dina Fourie.

Born in 1829 in another world and another time, in Cradock in the Cape Colony, Dina was but a little girl when her life of adventure started. When her parents joined the Great Trek to escape British rule, they packed their wagons and set out for the Great Unknown. They would boldly be entering the enormous African interior, which was still mostly marked as “unexplored,” even in those days. I’m sure her family and mine would have known each other, for they had camped out in the same region when the famous murders at Bloukrans (“Blue cliff”) and Moordspruit (“Murder-creek)” took place. While my family somehow escaped, the treacherous murder gangs of the Zulu king, Dingane, struck the Fourie laager unprepared and totally unexpected. They arrived in the darkness of night, while the laagers were fast asleep, and when they had gone, the wagons were aflame, and a total of nearly five hundred women, children, men and servants lay dead – horribly mutilated in most cases. Among them lay the mother of Dina Fourie and two other Fourie children – presumably her siblings or cousins. Dina’s mother had been stabbed with spears several times, and although she survived the initial attack, she never really recovered from her wounds and died not long after. When Dina and some of the other pioneers left, the “Promised land which flows with milk and honey,” as it had been called, Natal seemed like a cursed land to many. They were determined to make a new beginning in the Transvaal, which could only promise to be wilder than the beautiful and comparatively gentle region they had just left. Little did anyone know it, but by the time that Dina eventually would settle, she would have seen death in all its forms.

When Dina’s father married again, she moved in with her older brother to look after him until he got married. By this time, Dina Fourie must have lived to see the town of Ohrigstad being decimated by malaria, and she and her surviving family had moved on to the little town of Schoemansdal. The place is a ghost town today, but back then it was the ivory capital of the Transvaal and quite possibly one of the loneliest, wildest places in South Africa. There she fell in love and married an ex-British soldier called John Chambers. A large man with a mysterious past in the Indian army, but one who had a passion for life. At Schoemansdal, Chambers became a trader, and there too, they had their first child. But the birth did not bring happiness. Only a few weeks after the birth, the first child of Dina Fourie breathed its last and had to be buried in the red clay of Schoemansdal, leaving a young mother who still had not the faintest idea of how much grief she would yet live to taste.

The real trouble started in 1859. After the death of the old pioneer leader, Hendrik Potgieter, the president who took his place turned out to be one of the most obstinate, quarrelsome and downright difficult men whom the Transvaal had ever known. So much trouble arose, partly because of this man and his enormous ego, that a short and chaotic little civil war broke out. The notorious Stephanus Schoeman rushed out to join the war in Pretoria and, in so doing, made himself even more unpopular by commandeering all the supplies he needed from his helpless subjects and attempting to remove the town’s cannons for his personal use. Dina’s husband, John Chambers, was one of the men who joined forces to prevent Schoeman from removing the two cannons in the old clay fort, which protected the town from native attacks. Schoeman swore revenge on John Chambers and made him understand very clearly that he would be “back to settle unfinished business.” When the war was over, Schoeman returned as promised, and John Chalmers knew that he was in for a spot of very bad weather with the bitter and unforgiving Schoeman. Representing the military, as well as the judiciary, and being the president of his own little empire gave Schoeman the necessary power to really squash his opposition.

Along with one of the famous old big-name professional ivory hunters of his day, Jacobus Lottrie, Chambers decided to make a beeline for the Portuguese colony that is today Mozambique. The only problem was that he could not take the short route to Delagoa Bay (today’s Maputo) or Inhambane, because between him and the coast lived one of the most bloodthirsty and unreasonable tribes in the north. Manukosi, or Soshangane, was the successor of Zwide, the king of the Ndwandwe tribe that had been decimated by Shaka Zulu during the battle of Ndolwane. During this battle, Ndwandwe lost 30 000 men in one day, being almost wiped out in the process. Having been thus displaced, Manukosi and his successor, Mawewe, ruled like tyrants and had already wiped out an entire pioneer trek in previous years. For any white people to venture into Mawewe’s domain would have invited certain destruction.

The only alternative lay in following the ancient old trade route up to the old far-off coastal port of Sofala. The problem was that, together with the great distance, the region north of Mawewe’s empire was full of deadly tsetse flies and malaria. April is a particularly bad time for malaria, and an old hunter like Lottrie must have known that they would be rolling the dice with death. Yet, caught between the devil and the deep blue sea, as it were, they had no other choice. Lottrie himself had also angered Schoeman in some way, and they knew they had to get away fast. Accordingly, John Chambers set out with his wife and four children, and so did Jacobus Lottrie, with his wife and son.

Down the Levhuvhu River, they followed in the tracks of the wiped-out Van Rensburg trek, slowly hunting, prospecting and exploring as they went. But, as with the Van Rensburgs of old, death lay waiting in the feverish lowlands, extending its greedy fingers to welcome the unwary travellers with savage glee. Already greatly saddened at having had to leave her home, her best friends, and the grave of her firstborn child, Dina had to walk behind the two wagons most of the time, trying to explain to her little ones where they were going, and why. The rains continued until late that year, and crossing numerous rivers full of crocodiles and hippos must have been a nightmare. All the while it rained and rained. Nobody was surprised when Hannie Lottrie, wife of the romantic old elephant hunter, suddenly began shivering and fell prey to fever. Seeing the fear of death in her eyes, the bereaved old hunter read from the Bible to his wife, until she calmed down with the knowledge that she did not have to fear death any longer. She died shortly thereafter, and Dina Fourie helped to bury her in an unknown grave, simply wrapped in a sheet. There was no time to linger, for already the deadly tsetse flies began to settle on the oxen, and the party knew that, from there on, they would be in a race against death. Between them and Sofala lay a quarter of a thousand kilometres of some of the wildest, most dangerous and unforgiving wilderness known to man, and they knew they would not cross it without seeing much more death. Even as the oxen began to weaken as a result of the dreaded sleeping sickness, or nagana, the horses caught horse-sickness as everyone knew they would, and died with a last shudder. The little safari of fugitives was still fighting lions and sucking mud, when the feeble and sickly little thirteen-year-old son of Lottrie also caught fever. For some days, the fever raged. With a burning thirst and searing fever, he called to his mother in delirium, while Dina nursed him like her own child. And then, late one night, his candle also burnt out and the young boy quietly passed from this world. He, too, was buried in a little grave, lost to the memory of man in the immensity of the African wilderness.

By this time, the draught-oxen were also beginning to die. Every day the trek marked its progress by strings of provisions and equipment that were abandoned in a desperate effort to make the wagons lighter. When they crossed the Lebombo range, they were greeted by a level sea of bush that stretched as far as the eye could see. Between the mountains and the horizon, they knew, more certain death was grinning with unseen fangs. Through this never-ending maze of thirst and ferocious beasts, the crippled trek struggled along until, at the Great Save river, the last of their oxen died. From here on, they had to proceed on foot with whatever could be carried on their backs. Dina took the small hands of her little children. Maria, the eldest at five years of age, with the precious doll her unknown grandma had sent her from England, Jannie of three years, Josef, a baby of one year, and little Susan, only three months old. How they managed to carry arms, ammunition, food, blankets, and three babies is beyond the comprehension of any man. Nevertheless, they had long since passed the point of no return, and their only hope lay in trying to reach Sofala before they all died. And so they marched on beneath the burning sun, with mosquitoes, ticks and tsetse flies sucking indiscriminately at the blood of parents and babies alike. For Dina, the journey must have been agonizing. By this time, wasted by malnutrition and exposure, her milk had stopped flowing, and she could feed her babies no longer. Little Susan, she knew for sure, would die within the next few days.

Perhaps the only thing that saved little Susan and all of them from certain death at the time was the fact that John Chambers had, once upon a time, twice saved the life of the son of a local petty chief. Once by killing an elephant just before it trampled the boy, and the second time by sucking the poison from the young man’s stomach after he had been struck by a poisoned arrow. After all these years, Chief Chabane had never forgotten the kindness of the white trader whom he had originally rewarded with two elephant tusks. When he heard of the party’s distress, he immediately sent thirty bearers and some porridge and sour milk for the babies. They carried the tattered and weak fugitives to their village, and even managed to save the wagons and some of the lost gear. The kindness they received at Chabane’s village probably saved the lives of all; for now, at least, everybody could rest and recover. When they had regained their strength somewhat, Chabane sent them on under the leadership of one of his indunas, a brave man called Makakikiaan. With the children carried in litters, and living on the hospitality of scattered villages, the party moved on, crossed the mighty Chimanimani mountain range of eastern Zimbabwe, and bade Makakikiaan goodbye as he passed them on into the care of new porters. Here disaster struck again. Dina’s half-brother, David, who had accompanied the trek, suddenly fell ill to a mysterious disease. He was in constant, excruciating pain, and the symptoms were so mysterious that the new bearers promptly decided that he was a victim of witchcraft. Therefore, they simply deserted and left Chambers and Fourie to their fate. For days, young David Fourie wrestled with the pain of his “sinking fever” - together with malaria - hallucinating and asking whether he would also die like the other members of his family already had. This went on for two weeks, until John Chambers could do little more than sit at the young boy’s side and pray that he would be allowed the mercy of a quick death. When the boy finally died, he too, was buried, simply wrapped in a blanket.

After a lifetime of shock and disaster, poor Dina took the loss of her half-brother, who must have been like her son, very hard. With John Chambers finally sinking into a dark pit of depression and not being able to forgive himself for ever having picked a quarrel with his leader in the first place, Dina Fourie finally succumbed also, desperately pleading: “Lord, help me, I can go on no longer.” Ironically, though, Dina’s darkest hour also proved to be the turning point in her struggle. Although things were bound to get a lot worse still, Dina became a stronger person from that day onward. The first thing that happened after David Fourie’s death was that Francois Lottrie decided that he had had enough. He had been a loner all his life and was more accustomed to looking after himself only. He knew how to survive alone in the wilderness, but not with helpless women and children. So, the grief-stricken hunter announced that he was going to quit the journey to Sofala and go off on his own to go and do some prospecting in Banjiland. There he would eventually be deported by the Portuguese and sent back to Schoemansdal, from whence he had originally come. For Dina and John Chambers, however, the struggle continued. Struggling on as best they could, two wasted adults and four hungry, weak children, the miserable safari continued. A few days later, the little one-year-old boy, Josef, also died. When John Chambers and his family finally staggered into Sofala with only three children left, and four dead people buried behind them, they could scarcely believe that they had made the long journey alive.

In Sofala, John Chambers took an administrative job, working for the Portuguese governor and living in the local fort with his family. Life seemed to hold a little promise now, even though they could hardly understand the language or ways of the people amongst whom they were now living. In the meantime, Dina’s old father eventually found out about the misfortunes that had befallen his daughter and her family. He wasted no time in taking a wagon and going after Dina with a view of bringing her home. Once again, however, fate struck with savage cruelty. On the way, the old man caught pneumonia and had to be buried by his youngest son. His grave, at least, was marked by the story of how he had met his fate, for the boy managed to carve out the sad tale on the side of a nearby baobab tree.

At least the news about her father’s death and the failed rescue mission was something that Dina was temporarily spared from knowing. One day she accompanied her husband on a hunting expedition. She returned early, only to find to her horror that a ship infected with diphtheria had called, and that the infection had spread throughout the town and fort. A terrible epidemic was ravaging Sofala, and her children were already in it! Not being able to watch so many people suffer and die without treatment, Dina was resolved to place the fort under quarantine and to go to the aid of the townsfolk. For two weeks she received her food through a hatch from the fort. And then, one day, the food stopped. With a sinking feeling, Dina opened the doors to the fort. Inside, the Portuguese governor’s wife lay unconscious, with one of her children dead, but still warm, right beside her. All the other children, including Dina’s own, had caught the disease and were desperately ill. Dina then turned her attention to nursing the children, but despite her best efforts, the eldest son of the governor died, along with her and John’s eldest daughter, Maria. As if that wasn’t enough already, her little son, Jannie also died shortly after. With his dying breath, the little boy wanted to know when his father would be home. And so the Chambers family was left with only one child alive. With John Chambers and the governor unaware of the epidemic, Dina herself had to bury all her children, as well as those of the governor.

It seems that life can sometimes be incredibly unfair to some individuals, almost as if it targets them specifically for no reason we can understand. Perhaps this was the case with Dina Fourie, for the following year, she and her husband and their last remaining little daughter, Susan, embarked on a ship to go on a trading journey up the coast. After some days of calm weather, the ship got caught in a tremendous storm that left everybody helplessly seasick. When calm returned, little Susan was no more. After years of hardship, her frail little body could simply not take the last strain and dehydration. So the family was finally reduced to only the original two –John and Dina. Old Africa had a curious way of sometimes making or breaking people. It left few of its old pioneers untouched. By this time, John Chambers must have realized that Africa had broken him. He had lost his home and property, his entire business, his friends and his entire family, except for his trusted wife. It was time to quit. It was decided that the two of them would sail for England to spend some time with John’s parents and to re-evaluate their shattered lives. In order to pay the passage, however, John found it necessary to return to the two old wagons he and Francois Lottrie had abandoned at Chabane’s village on their original journey. The plan was to remove the iron and steel from the wagons, so that these could be sold for passage to England. Chambers set out alone on this journey, but that year the rain came early and, along with it, the fever. As he reached Chabane’s village, he suddenly collapsed with cerebral malaria. With the white man delirious, Chabane sent his trusty old Makakikiaan to fetch Dina, who was still waiting for her husband’s return in Sofala. When Dina saw the safari coming, she must have known there was trouble, even though they wouldn’t tell her what had happened. She hurriedly bade the new governor goodbye and set off to help her husband.

The journey back turned out to be a nightmare beyond description. Before they knew it, Makakikiaan and his men, together with Dina, found themselves trapped between the raiders of the cruel Mawewe and some desperate Ndebele tribesmen who had recently been displaced by the infamously violent and murderous warlord, Mzilikazi. They were severely humiliated by Mawewe’s warriors and had to buy their lives back by offering gifts, all the while travelling by night, having to live off the land and not daring to make any fires. Extreme hunger, lack of food, constant rains, and great exhaustion soon took their toll. It was only a matter of time before Dina also collapsed with fever and had to be carried by her escort, half-conscious, for much of the way. The countryside was littered with lions, and at night, the exhausted tribesmen had to cover Dina’s unconscious figure with thorn branches to keep her safe. Still, one night an old and “toothless, man-eating lion” managed to grab Dina and drag her away. It was only by great fortune that Makakikiaan managed to rescue her by going after the lion and killing it.

Dina eventually recovered somewhat, but she was too late. When she reached Chabane’s village, John Chambers was no more. They could only point out the fresh heap of soil where he had been buried, days before. Now at last, Dina Fourie found herself utterly and completely alone in the world. There was no hope of returning to Sofala, and she could also not remain with Chabane, because his village was caught in a desperate famine, following the terrible Ndebele raids. Even the journey back to Schoemansdal seemed like a suicide mission, because it would lead past Mawewe’s heartland, and she had no way of knowing how president Schoemand would receive her. Far to the east was only the Indian ocean, and to the west, across the Chimanimani, the land where Mzilikazi conducted a reign of terror.

Dina chose to return to her people in Schoemansdal, travelling by night and with only famine rations, wild food, and the kindness of Makakikiaan to keep her alive. It was a journey that would ultimately take five months to complete. Dina travelled much of it in a litter, beside herself with fever. The crossing of the flooded Save River, on a flimsy raft built of tree bark, was a near-disaster. When Dina and her escort reached the opposite bank, they had escaped with nothing but their lives. They lost all their possessions in the angry river. Now Dina Fourie stood in the world with nothing more than the tattered remnants of her torn and worn clothes. Even the English doll of her daughter, Maria, had been swept away. She had nothing left to lose except her life. But there would be one more blow before it would be over. A few days later, Makakikiaan ordered a halt to the safari at a place where curious markings had been left in the soft bark of a baobab tree. For the first time Dina had to read how her father had also died in his quest to save her!

Mercifully, she was too fever-ridden by this time to fully appreciate the fact. Carrying and dragging the dying woman, Makakikiaan and his men finally came to the Limpopo River, which they swam, dragging Dina along past crocodiles and hippo without number. On the other side, Dina lay between life and death for a week before they could drag her further towards the distant hills. By this time she had scratched a message on a piece of bark, which one of the tribesmen had carried on ahead, so that one day when she opened her eyes, it was to see European faces that had come to rescue her!

Dina Fourie took many long months to recover. First at the famous Joao Albasini’s fort, and then at Schoemansdal. Even as she was shaking with fever, however, she managed to make sure that Makakikiaan and his men would receive a large reward. Rattling and shaking, she took the black man’s hand in hers and brought it to her mouth, thankfully declaring: “Makakikiaan, your hand is black, but your heart is white. Snow-white. I truly thank you…” And with that, the dark-faced tribesman gave her a raised salute and vanished into the featureless wilderness from whence he had come to save the woman of a dead man who had, once upon a time, saved the son of his chief.

The amazing life story of Dina Fourie didn’t end here, though. Months later, she had a meeting with general Schoeman, and although nobody was present to tell how it had went, it is known that when it was all over, they had become reconciled again. At 34 years of age, Dina eventually married Johan Heinlein, a Swiss immigrant, and together they still had three sons and a daughter. Both lived a long and fulfilling life. In 1899, the Anglo-Boer War broke out, and Dina lost everything once again. Her home, her property, and the life of her husband, who fell as a warrior during the Battle of Rooiwal at the advanced age of 75 years! She herself lost her freedom when she was railed off to a concentration camp, where ultimately 25 000 to 28 000 Boer women and children would die as a result of disease, starvation and neglect. But by that time, it probably didn’t matter much anymore. During her lifetime, Dina Fourie had learnt how to handle loss, and when the time finally came for her own life to be added to the list of concentration camp deaths, I could imagine that she might have been happy to know that her life would be the very last thing she would ever lose.

Many times when things go wrong, I think of Dina Fourie. Those who knew her declared that she always had limitless time to help others, never became bitter, and above all - to the end of her life - she is said to have always remained deeply thankful for every little thing that she had in life. Indeed, we sometimes have to lose what we have in order to appreciate it most. When I think of the life of Dina Fourie, the familiar expression comes to mind: “When you come to the end of your rope, tie a knot and hang on.” I think Dina did that, perhaps more than anybody I know.

Viewed: 3321

|

|

Tweet |

-

Ben se skielike dood kom as groot skok

26 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Rotariërs maak bittersoet laaste skenking aan Bergcare

26 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Raliphada finally gets appointed as CFO of Makhado

26 July 2024 By Kaizer Nengovhela -

RAL says work did not stop on busy R522 road

26 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Koben droom steeds groot

26 July 2024 By Karla van Zyl

Anton van Zyl

Anton van Zyl has been with the Zoutpansberger and Limpopo Mirror since 1990. He graduated from the Rand Afrikaans University (now University of Johannesburg) and obtained a BA Communications degree. He is a founder member of the Association of Independent Publishers.

More photos...

Big-game hunters such as Jacobus Lottrie, who travelled with the group to Sofala, would have made use of small wagons such as this. Photo from the Cuénod private collection.

The graveyard at the Schoemansdal heritage site.

The last name on the graveyard inscription at the Schoemansdal site reads "Baba Chambers - 3 weke oud" (Baby Chambers - Three weeks old).

ADVERTISEMENT

-

MMSEZ pushes for township development

12 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Sheryl chosen again to represent Team SA at Paris Paralympics

12 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Is Musina a gravy train for officials and councillors?

19 July 2024 By Anton van Zyl -

'Waterless' Vhembe causes problems for Phelophepa Health Train

27 June 2024 By Thembi Siaga -

Fuel company remains closed after SARS raid

18 July 2024 By Andries van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT:

ADVERTISEMENT