14. The meeting place of opposing ideologies

Date: 22 December 2016 Viewed: 24747

For this week’s chapter, we return to one of the older streets in town, namely Rissik Street. Rather unimaginatively it was named after yet another land surveyor, Johann Friedrich Bernard Rissik. Not that he was a person without flair, or that he did not deserve to have a street named after him.

He was, after all, the man who had helped to identify the area that we now know as Johannesburg (and hence it was also partly named after him). It is just that Rissik did not have a big presence in the Soutpansberg. It was thus more of a challenge to find a local angle and incorporate some of the region’s fascinating stories into this chapter.

Difficult as it may sound, we did manage to find a story that has all the elements of a Hollywood blockbuster movie. It is a story of a hero who turned villain; it is about politics, war, espionage, a famous court case and the eventual acceptance of a status quo. However, before continuing to the “local” story, we need to briefly talk about the man Rissik; after whom the street had been named.

Johann Rissik was born in Holland in 1857 in Linschoten, near Utrecht. His father, Dr Gerrit Hendrik Rissik, was a physician and surgeon. In 1875 the then president of the ZAR, TF Burgers, was on a visit to Holland where he met Dr Rissik. He was so impressed with the doctor that he invited him to come to South Africa and work as the District Surgeon and as the president’s physician. Dr Rissik agreed and the young Johann, who at that stage was already fluent in Dutch, English, German and French, joined him on the journey.

At first Johann worked as an assistant in his father’s dispensary in Pretoria, but it was clear that medicine was not his great love. On 25 February 1882, he received his first appointment as land surveyor when State Secretary W Eduard Bok approved his position as second government clerk in the Surveyor-General’s office. His salary was a very reasonable £200 per annum.

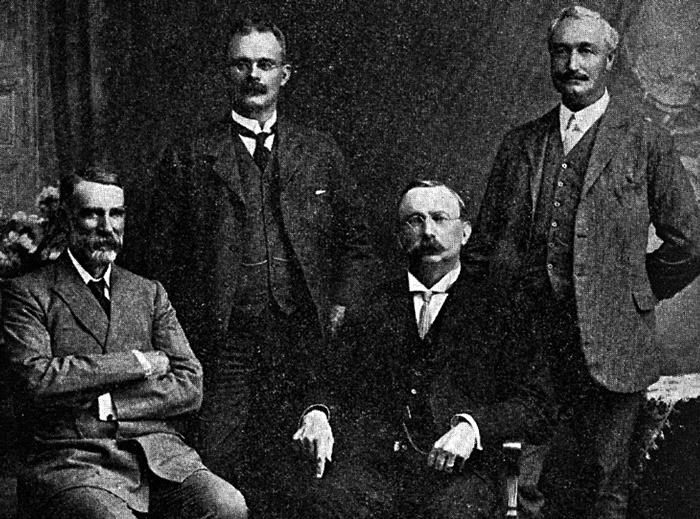

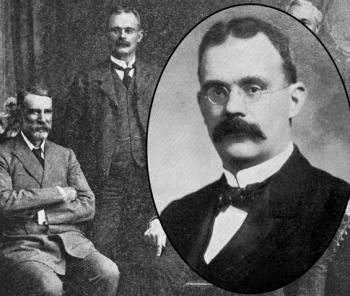

The first Provincial Administrators, 1910. From left to right: Mr Smythe (Natal), Johann Rissik (Transvaal), Sir Frederick de Wool (Cape), and Mr Ramsbottom (Orange Free State).

Probably one of the most important contributions Rissik made to the country, happened in 1886. Along with Christiaan Johannes Joubert, he was appointed to investigate the Witwatersrand farms that were to be proclaimed as gold diggings. The two of them also had to decide on the place where a town was soon to be established. On 12 August 1886, they handed over a lengthy report to the President and Executive Council. One of the interesting recommendations made, was that the goldfields should not be thrown open without reservation for general pegging of claims, but that mining leases should be granted to the owners and lessees of the land. They also recommended that a piece of land situated between the farms Turffontein and Doornfontein, known as Randjeslaagte, be developed as a new town. This would later become the city of Johannesburg.

Rissik played an important role in setting the boundary between the then Transvaal and Mozambique, way back in 1887. On instructions of the ZAR government he met the Portuguese representative, Col Machado. After a survey the two established the beacons of what is still today the border between two countries.

On 8 October 1890, a rather important ceremony took place (at least for the purposes of our story). Johann Rissik married Maria Magdalena Wilhelmina (Mimmie) Leibbrandt. She was the sixth child of Pieter Ulrich Leibbrandt, the son of Johann Sebastian Leibbrandt. Mimmie’s uncle was Abram Johannes Leibbrandt, father of another Johann Sebastiaan Leibbrandt. His son was Willem Theodore van den Berg Leibbrandt and his grandson Meyder Johannes Leibbrandt. Meyder’s son was the infamous Sidney Robey Leibbrandt, the subject of our extended story.

Before explaining why Robey Leibbrandt is important to the history of the Soutpansberg, we first need to finish the story of Johann Rissik.

Johann and his wife, Mimmie, lived in a very imposing homestead “Linschoten” in Pretoria for 33 years, raising four sons. The eldest, Bernard, was killed at Flanders in 1915 during the First World War. The couple were very popular and their friends included people such as the well-known author, Percy Fitzgerald (of Jock of the Bushveld fame) and General Louis Botha.

Rissik did come “close” to the Soutpansberg in an official capacity in 1899 when the Anglo Boer War broke out. He was appointed by Genl Schalk W Burger to serve as a member of the Special Court for the districts Zoutpansberg and Waterberg; and to try a man for high treason. Rissik respectfully declined this appointment, arguing that he lacked the legal training to be able to do this. Ironically Rissik was quite knowledgeable as far as legal matters were concerned and played an important role in establishing the country’s mineral rights laws.

Rissik served his country in various capacities for the next few decades. He was elected as Member of Parliament representing the Het Volk party in February 1907. (He, along with Genl Louis Botha and Genl JC Smuts helped form the Het Volk party in 1907; which contested the first general election under Responsible Government). In March 1907, he was appointed Minister of Lands and Minister for Natives in Transvaal. When the Union of South Africa was established in 1910, Rissik became the first Administrator of the Transvaal.

As a businessman he partnered with prominent people such as Loftus Versfeld and JJ Marais. He was associated with the establishment of the Pretoria Portland Cement Company and later with the Delfos Brothers in forming the Pretoria Iron Mines, which later became Iscor (and currently Mittal Steel).

Perhaps the last piece of interesting history about Johann Rissik is that he is said to have owned the first motorcycle in Pretoria. He was also very interested in aviation and became the first president of the Aeronautical Society of SA.

When he died on 26 August 1925, messages of sympathy streamed in from across the globe. The pallbearers at his funeral included his friends, Genl Smuts, Judge JS Curlewis, Sir Julius Jeppe, Sir Johannes Wessels and his brother-in-law, Pieter Ulrich Leibbrandt.

This then brings us back to the Leibbrandt who is the subject of the second part of this article, namely Sidney Robey Leibbrandt.

The Leibbrandt story made headlines throughout the world, especially in the first part of the 1940s. An important chapter of this history plays off in the Soutpansberg, where he, as a fugitive on the run from the Smuts government, was hiding in the western peaks of the Soutpansberg mountains. Leibbrandt even left a “legacy” here, by (presumably) carving out a swastika symbol in a small rock shelter, secluded in thick bushes.

For the sake of the readers not knowing who Robey Leibbrandt was, we have to start at the beginning, which is in Potchefstroom in this case, where he was born on 25 January 1913.

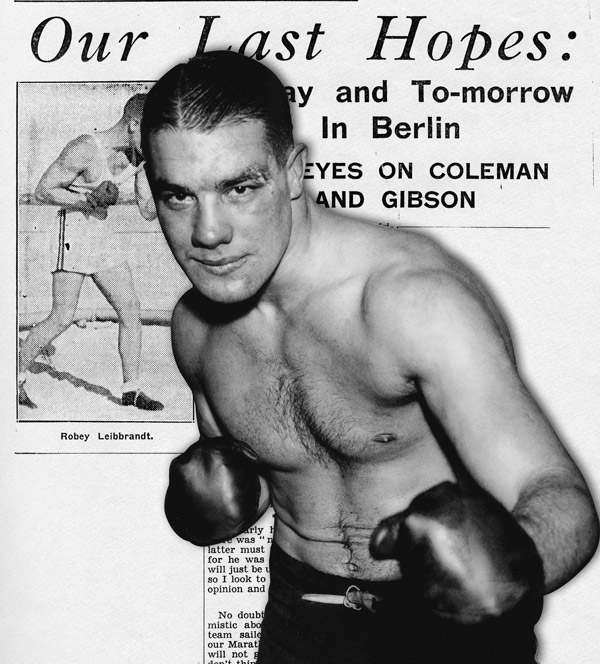

Left: Robey Leibbrandt after he was let out of prison. Right: Leibbrandt was the South African Heavyweight Champion that represented South Africa at the 1934 Empire Games. (Source www.leibbrandt.com)

His father, Meyder Johannes (“Oom John”) Leibbrandt, fought alongside Genl. Jan Smuts in the Anglo Boer War, but was never active in politics. The early political influence in Robey’s life may have come more from family members on his mother’s side of the family. Susan Marguarite (née Joyce) was of Irish descent and her brother was the well-known clergyman, Ds William Robey Joyce. During the Second World War a cousin of hers’, William Joyce (better known as Lord Haw-Haw), caused a stir by broadcasting Nazi propaganda. He was arrested after the war and following a trial he was sentenced to death. He was executed in England. From Robey’s own memoirs it is clear that he had a lot of admiration for his uncle.

Robey started boxing competitively when he was still a scholar at Grey College in Bloemfontein. In 1934, at the age of 21, he won a bronze medal for South Africa at the British Empire Games in London. Two years later, in 1936, he took part in the Olympic Games that were held in Berlin. In spite of seriously injuring his hand in his first match, he went on to finish fourth. He narrowly lost in his last match against Roger Michelot, who would continue to claim gold in the light heavyweight class. Leibbrandt became South African heavyweight champion on 31 July 1937 in Johannesburg, beating Jim Pentz.

Short video clip showing Leibbrandt preparing for the 1934 Empire Games. (Source: www.leibbrandt.com)

The Berlin Olympics played an important role in Leibbrandt’s life, as it exposed him to Nazi Germany and one of his greatest heroes, Adolf Hitler. After the games, he returned to Germany and among other things studied at the Reich Academy for Gymnastics. When war broke out, he joined the German Army and became the first South African to be trained as a “Fallschirmjäger” (para-trooper). His later military training included sabotage training at the infamous Abwehr school.

While this was all happening, back at home General Jan Smuts had sided with the Allied Forces. Germany was, understandably, not very content with the state of affairs. The fight for the then German colony, South West Africa, was still very much relevant and Hitler was very aware of the strategic mineral wealth that southern Africa offered. Foreign Minister Von Ribbentrop was instructed to increase espionage and propaganda activities in these territories, where there were many German sympathisers.

South Africa declared war on Germany on 4 September 1939, but there was an anti-war faction in the country. The most vociferous were the Purified National Party and the Ossewa Brandwag, headed by Dr Hans van Rensburg. Van Rensburg was also suspected of being a double agent on Smuts’ payroll. The Germans believed that the elimination of General Smuts would act as a catalyst to unite the country against the pro-war party.

A plan for a coup d'état to overthrow the SA government was devised and in 1941 Admiral Wilhelm Canaris ordered Operation Weissdorn. Part of this plan entailed that Leibbrandt (under the pseudonym of Walter Kempf) would be sent to South Africa to muster support for the German ideals and set the plans in motion. Leibbrandt left Germany on 5 April 1941 on a confiscated French sailboat (the Kyloe) and completed a journey of over 9 000 miles, to be dropped off the coast of Namaqualand. On board was a radio transmitter and a significant amount of American dollars to help Leibbrandt with his mission. The longer journey was necessitated by the danger of running into British ships. On 15 June 1941, a drenched Leibbrandt (his inflatable boat had capsized close to shore) arrived on SA shores and he started to make his way inland.

We unfortunately have to skip past many interesting bits of the history, such as his journey through the desert and his efforts to make contact with the leaders of the Ossewa Brandwag (OB). He did eventually meet with Dr Hans van Rensburg, leader of the OB near Pretoria. It quickly became clear that the two men did not share the exact same ideals and Leibbrandt had no faith in the leadership abilities of Van Rensburg.

Leibbrandt felt a need for action and started to canvass supporters for his own ideals. He formed the Nasionaal Sosialistiese Rebelle, and in secret meetings started drumming up support. Those who took the secret blood oath were trained in sabotage methods such as making bombs. Members of the “militant” wing of the OB, the Stormjaers (Storm Troopers) took a liking in his radical pro-Nazi philosophies and some 60 fighters joined him. This, naturally, started attracting the attention of the authorities and before long Leibbrandt had to go into hiding.

At that stage the government had heard rumours that Leibbrandt was back in the country, but it was not yet official. Leibbrandt, on the other hand, battled to make contact with Germany and without specialist knowledge the radio transmitter that he had brought along from Germany, was of little use. Leibbrandt and one of his staunchest followers, Karl Theron, recruited a radiographer from Potchefstroom and tried to contact Germany from a farm near Warmbaths (Bela-Bela). When this did not work Leibbrandt and Theron opted to move further north to the farm, Ontmoet, in the western Soutpansberg. The farm belonged to Andries van der Walt, also an OB member, who was sympathetic towards their cause.

The farm where Leibbrandt and his helpers fled to, was ideal for a variety of reasons. It was extremely secluded and it was adjacent to the highest peak in the Soutpansberg. Here they tried to erect the mast for the radio sender, but again could not succeed in making contact with Germany.

Even in the most remote areas word travels fast and the police at Mara (just below the farm), heard rumours of strange men carrying heavy equipment up the mountain. Three of Leibbrandt’s men returned to Johannesburg after the second unsuccessful attempt to contact Germany by radio, leaving Leibbrandt and Theron at Ontmoet. The two of them very brazenly even attended a function at one of the nearby farms, with Leibbrandt introducing himself as Mr Lubbe.

On 11 September 1941 Leibbrandt was warned by Andries van der Walt (junior) that the police at Mara seemed to have gotten wind of some strange activities on the farm. The two were on high alert, but were fast asleep under some trees when a police delegation, led by Sgt Christiaan Pauley, arrived at the peak the following morning and found them. Constable Willem Beetge managed to disarm them, but some confusion reigned, especially after another of the police officers, Sgt Jacobus Kruger, recognised Leibbrandt. The police, not really knowing what to do with the men (as there was at that stage no warrant out for the arrest of Leibbrandt), eventually had to let the two men go.

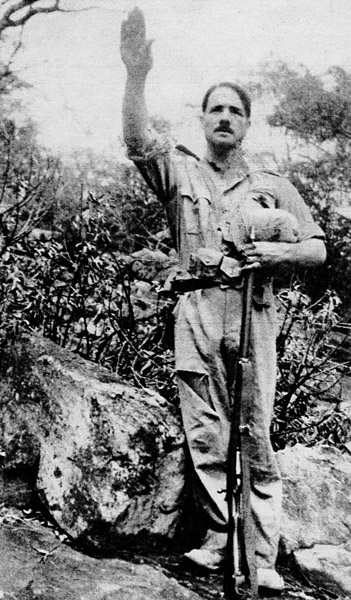

Left: Robey Leibbrandt giving the German salute while hiding at the farm of Mrs Eggert in the Magaliesburg mountains. Right: Robey Leibbrandt giving a salute outside the court after being sentenced. (Source: www.leibbrandt.com)

Leibbrandt was very upset with this “traitorous” act and was determined to punish the people who had betrayed them and told the police about their whereabouts. Not long afterwards he heard that two local farmers, Coetzee and Dames, acted as informers. Before leaving the Soutpansberg, he decided to teach them a lesson and drove to the farm Goedgedacht of Coetzee. After luring (whom he had thought was the correct) Coetzee out to the road, he proceeded to give him a severe hiding with a sjambok, so much so that Coetzee had to spend several days in bed recovering. Coetzee’s pleas that he knew nothing of the events fell on deaf ears. Leibbrandt only later realised that he had assaulted the wrong man.

Leibbrandt then went to the farm of Johnstone Dames. Dames’ brother-in-law, an Air Force officer Anderson, was on a visit at the farm. Leibbrandt again lured them out to the nearby road and after threatening to shoot them, assaulted them severely. It was only the timely intervention of Mrs Dames, armed with a shotgun, that saved these two men’s lives. After some exchange of fire, Leibbrandt and his colleagues fled for Brits.

Leibbrandt evaded arrest for a few more weeks, but now the whole of the country’s security forces were hot on his trail. A reward equivalent to R1 000 for his capture, dead or alive, was put out. After a skirmish with the police, he fled to Magaliesburg where he was assisted by people who were sympathetic towards his cause. At the end of December 1942, he was finally captured and arrested in Pretoria. The arresting officer was Claude Sterley, a fellow Springbok boxer. Leibbrandt, even though he was armed, did not put up a fight in order to avoid a bloodbath.

In one of the most talked about court cases in the history of South Africa, Robey Leibbrandt was charged with treason alongside 16 others. The case was first heard in camera in police cells. When he was asked to say something in his defence by the presiding officer, he confirmed his commitment to the ideals of Adolf Hitler and that of National Socialism. He and six others were found guilty and the case went to the High Court. Leibbrandt refused to testify in the case, but maintained that he was innocent. On 11 March 1943, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. Only two of the other accused, Le Roux and Olwage, were found guilty on minor charges and sent to prison for a period of five years.

The Leibbrandt case went on appeal and much to the surprise of everyone, he handled his own defence. This was not very successful and the Appeal Court confirmed the Higher Court’s decision. The time lapse did help him though, as it became clear that Germany was losing ground in the war in Europe. In December 1943, two days before Christmas, Leibbrandt was informed that General Jan Smuts, who had great sympathies for the Leibbrandt family, decided to commute his sentence to life imprisonment.

The winds of change swept through the country in the following years and in 1948 Leibbrandt was released in an amnesty deal for war offenders by the newly victorious National Party Government. Their leader, Dr DF Malan, had previously opposed South Africa's entry into World War II and wanted to remain neutral. Leibbrandt left the prison and was greeted by the crowds as a hero.

In later life Leibbrandt remained politically active and he founded the organisation Anti-Kommunistiese Beskermingsfront (Anti-Communist Protection Front) in 1962. He produced a series of pamphlets titled Ontwaak Suid-Afrika (Wake up South Africa). His love for sport remained and he was a passionate hunter. Leibbrandt was married to Margaretha "Etha" Cornelia Botha and they had four sons: Hermann, Remer, Izan, and Meyder Johannes and one daughter, Rayna.

Robey Leibbrandt died on 1 August 1966 after a heart attack. The request by family and friends from around the world to let him be buried with full military honours was denied by the South African government.

The swastika, carved out in a rock shelter on the farm, Ontmoet, in the Soutpansberg.

The area where Leibbrandt and his colleagues stayed in the Soutpansberg while avoiding the authorities, is now part of a nature reserve. The late Ed Eastwood, well known rock art specialist, visited the area in the early 2000s. In his book Capturing the Spoor, he writes about a remarkable discovery at the site:

“In 1998, a ranger on a routine patrol came across a rock shelter near the ruined foundations of Leibbrandt’s hut. He told us only that engravings had been found and that we should investigate the matter. When eventually we got around to visiting the shelter as part of the survey of that area of the Soutpansberg, we made an interesting and rather menacing discovery.

In a relatively small rock shelter secluded in thick bushes we found a deeply abraded image of a swastika, an ominous reminder of fascist designs on the world and, perhaps, a reminder of the now-defunct apartheid regime. One imagines that Leibbrandt, or possibly one of his followers, had proudly cut this image into the rock in order to invoke the ideal of a world of conformity. The swastika, a chilling and violent emblem in the midst of an area full of the gentler symbols of the San religion, highlights two opposing ideologies – one of extreme social control, the other of egalitarianism and individuality.”

Sources:

* Eastwood, Edward and Cathelijne. Capturing the Spoor, An exploration of Southern African Rock Art. New Africa Book, 2006.

* Strydom, H, Vir Volk en Führer, Jonathan Ball Uitgewers, 1983.

* Le Roux, JH, Robey Leibbrandt, Die Rebel, Instituut vir Eietydse Geskiedenis, UOVS, Bloemfontein, 1976.

* Pretoriana, MAGAZINE OF THE OLD PRETORIA ASSOCIATION, Published December 1965.

* Robey Leibbrandt vertel alles in Geen Genade, Bienedell Uitgewers (unknown date)

-

14. The meeting place of opposing ideologies

22 December 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

13. JC Krogh – The maker of peace?

28 October 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

12. Tracing the origins of the first Indian traders in the Soutpansberg

30 September 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

11. The (secret) story that started with Piet Retief

01 August 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

10. The times were a’changin for a controversial president

20 June 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

-

8. The casualties of war for the souls of the Soutpansberg

18 April 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

7. Bvekenya Barnard - the most famous of Crook’s Corner’s elephant hunters

21 March 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

6. The Englishman who helped shape the course of the country’s laws

29 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

5. Piet de Vaal, the stately “baobab” of the Soutpansberg

15 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT