4. The Boer general who didn’t like to fight

Date: 25 January 2016 Viewed: 24748

Our story of probably the most famous general in the history of pre-1900s South Africa starts with a mystery. Perhaps one should even say a conspiracy theory. Was this Boer leader, who served as president of the Transvaal Republic at one stage, an American by birth?

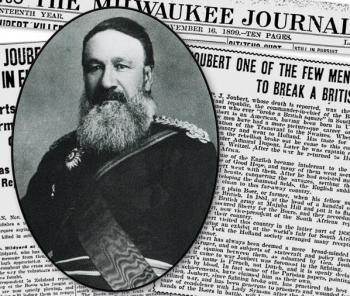

Often when one does research, one starts “at the end”. One looks for the obituaries and then trace back the links. In the case of Petrus Jacobus Joubert, such an obituary appeared in the Milwaukee Journal on 16 November 1899. The main heading of the paper that day reads “Gen. Joubert killed in fight at Ladysmith – Reports from Durban and Pietermaritzburg That Great Commander is Dead.” In the accompanying obituary, he is described as “an American, having been born in Uniontown, Pa, in 1841…” The newspaper further claims that he left the United States at the age of 14 for Holland. He returned in 1861 to take part in the US Civil War, among others as a captain of a coloured company under Gen. Weitzel. “After the war, he returned to Holland, and later went to South Africa.”

Contrary to what some may believe, newspapers can’t always be trusted. It is often well worth cross-checking the facts and trying to move closer to the truth. If the Milwaukee Journal’s reporter had his (or her) facts correct, it would mean that South African history as we know it may need a total rewrite.

The first problem with the Milwaukee Journal’s story arises with the announcement of his death. According to more reliable sources, the famous hero of many battles did not die on 9 November 1899, as the newspaper indicates. He died a few months later, on 28 March 1900, at his home in Pretoria.

In a very comprehensive biography on the life of Joubert, Johannes Meintjes* writes that the 69-year-old general probably died from peritonitis (a bacterial infection often caused by the rupture of an abdominal organ). This was mostly due to an incident on the battlefield around Ladysmith at the start of the Anglo Boer War. Joubert’s horse had apparently been frightened by an exploding shell at Beacon Hill. The animal stumbled, threw off the general and fell on top of him. Even in his injured state, Joubert still managed to control much of the early war period, but he and his wife, Hendrina, gradually had to make their way back to Pretoria.

Joubert was given a State funeral and tributes streamed in from across the globe, among others from Queen Wilhelmina (the Dutch monarch). The people who attended his funeral at his farm in the Wakkerstroom district included dignitaries from across the country. The guests present included many representatives from tribal authorities who, as Meintjes writes, “walked for many miles to pay their last respects.”

Piet Joubert’s whole life was one of contradictions. He was best known as the republic’s commandant general, a position he held for more than 20 years. Still, it is a position he seemingly never wanted and he went through great efforts to avoid war. When all negotiations failed and issues had to be settled on the battlefield, he remained a perfect gentleman and was well respected for this. His character was very well described by Sir George White, the defender of Ladysmith, when he called him “a soldier and a gentleman, and a brave and honourable opponent”.

In order to understand why Piet Joubert commanded such respect from all, even his enemies, we should probably now turn back the clock and look at where he came from. The Milwaukee Journal’s claim that he was born in 1841 is a bit dubious. That would have meant that his political career had started at the age of 19 when he was elected a member of the Volksraad for Wakkerstroom in 1860. (He initially refused this nomination). His real date of birth is more likely to be 20 January 1831, when he announced his arrival at the farm Damaskus at the present-day Prince Albert in the Western Cape. His ancestors arrived in the Cape Colony in 1688, when Pierre Joubert and his wife, Isabeau Richard, emigrated from De la Motte d’Aigues in Provence, France. Piet Joubert was the eldest son of Jozua Francois Joubert and Ester Maria Gouws, a couple that joined the Great Trek to the north when Piet was only six years old.

However, a bit of doubt still exists. Meintjes writes that, in spite of Joubert’s voluminous writings later in his life, he showed little interest in his childhood and youth. When Joubert was 12, his father died, followed a few years later by his mother. Could it be that a young American boy entered the country and took on the identity of such an “orphan”? Unlikely, but we can get back to the conspiracy theory later on.

Let us skip past Joubert’s somewhat traumatic childhood years and his education. As Joubert later remarked: “Whatever knowledge I have, I gained on the road of experience.” It is, however, worth mentioning that he taught himself Roman Dutch Law and served as a law agent in the lower courts. Apart from Afrikaans, Dutch and English, he could speak several of the indigenous languages. He acquired the nickname “Slim Piet” in reference to his exceptional knowledge on a wide range of subjects.

At the age of 20, Joubert married a rather extraordinary woman, Hendrina Johanna Susanna Botha. She was described as “utterly unafraid, inventive and tough” and she accompanied her husband on all his campaigns, gave military advice and shared his life up to the end. We will return to “Tannie” Drienie at a later stage as she also played a significant role in shaping the history of the Soutpansberg.

The Joubert couple began their farming life in the Marico in 1851.

In 1853, they moved to Utrecht, but settled in the Wakkerstroom district around 1856 where Joubert acquired a farm. This is also the period in which Joubert was drawn into the politics of the day (and there were many squabbles). In the biography about Joubert, Johannes Meintjes provides a wonderful summary of Joubert’s character, which also explains his later interaction with feuding groups in the Soutpansberg:

“The strife among his people, which was even to lead to a minor civil war, was upsetting to Joubert. Although so strongly individualistic, he was always ready to listen to another’s opinion and keen to find a peaceful solution rather than argue. As we know, the sound of battle reverberated in Joubert’s ears from early childhood, but he could hardly have expected that it would do so all his life. And he hated it. When pushed into a fight, he fought well, but he preferred to stay out of a scrap rather than become involved in it. Though by no means a coward, Joubert found physical violence repugnant. Like many pacifists he was more courageous than the war-mongers, and as he grew older, so did his pacifism deepen.”

Piet and Hendrina Joubert worked hard and made a success of their farming activities. His constant quest for knowledge meant that he was highly rated as a farmer and businessman.

For the purpose of this series of articles, we’ll have to skip past most of Joubert’s notable experiences. These include the First War of Independence, the battle at Majuba, the Jameson Raid and numerous tribal battles. We also skip past his 14 months at the helm of the Transvaal Republic and his almost two years’ service as part of the Triumvirate, along with Paul Kruger and M.W. Pretorius. We need to get to the Soutpansberg and his initial confrontation with the king of the Vhavenda, Makhado.

The well-known Venda historian, Dr M.H. Nemudzhivhadi, describes several visits by Joubert to the Soutpansberg. In December 1884, Joubert, in his capacity as Superintendent of Native Affairs, visited the area to try and diffuse the tension between Commissioners Oscar Dahl, Antonio Albasini and Makhado. As usual, the grievances concerned the non-payment of taxes and Makhado’s refusal to allow land surveyors to demarcate the land. Joubert wanted to avoid direct confrontation, in spite of the pressure from the local Boer forces. Makhado was also clever enough to play the different sides off against each other. Commissioner Albasini felt that Oscar Dahl was not doing his job in collecting taxes from Makhado, but a large part of the area inhabited by the Vhavenda fell under Albasini’s “jurisdiction”. Makhado capitalised on the confusion and indicated to Albasini that it would not be practical to “serve two masters”.

Joubert eventually left the area with a half-hearted promise that Makhado would allow his people to be counted, but that Albasini should take responsibility for the area.

(In part 2 we continue with the story of Piet Joubert, when we look at the role he played in the war against Mphephu, as well as the eventual proclamation of the town.)

Sources:

Meintjes, J. 1971. “The Commandant-General. The Life and Times of Petrus Jacobus Joubert of the South African Republic, 1831-1900.” Tafelberg Uitgewers.

Nemudzivhadi, M.H. 1998. “The Attempts by Makhado to Revive the Venda Kingdom, 1864-1895.” Potchefstroom University for CHE .

Nemudzivhadi, M.H. 1977. “The Conflict between Mphephu and the South African Republic (1895-1899).” Master’s Thesis - Unisa.

PART 2

Early in 1887, Piet Joubert was again asked by the local groups to intervene and act against the dissenting Makhado. Joubert tried to take a tougher stance this time, but it was also clear that he never fully understood the Venda culture and the manner in which they regarded ownership of land.

A transcript of the meeting that took place on 23 February 1887 gives some interesting insight into the manner in which Joubert viewed the inevitability of the expansion to the north. He discusses with Makhado the influx of people from the goldfields and says: “Nu daardoor worden de eigenaar van gronden uitgedrukt naar hunne plaatsen en zullen natuurlyk ook hier heen komen en daardoor kan … oneenigheid ontstaan.” (This leads to property owners’ being pushed away from their land and they would naturally also come here. This may lead to unrest and fighting over land.)

Joubert explains the necessity of having the land properly demarcated, so that the government can ensure that native people are not suppressed. “… dan zal het Gouvernement er dadelyk naar zien en … den overtreders strafe.” (The Government will then notice and act against the perpetrators).

The issue of land demarcation was contentious as Makhado again reiterated that “all land was that of Ramabulana.” Historians like Nemudzhivhadi explain this by pointing out that the Vhavenda king does not own any land, as it belongs to his mahosi. The king rules over the various chiefs and as such “all” land belongs to him as representative of the people. Makhado, however, was very concerned about the encroachment on the area in the valley below the mountain: “Nu weet ik zelf niet want vroeger was het geheele land Ramapoelanie zijn, maar een ding is zeker, ik wil niet onderste veld nich verliezen.” (Now I don’t know, because earlier all land was Ramabulana’s. One thing I know is that I don’t want to lose the fields below.)

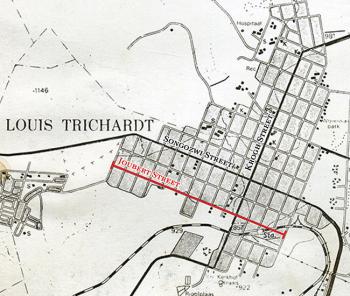

Following this meeting, Joubert came under more pressure not to allow Makhado’s request that such a vast area be demarcated for the Vhavenda. In Boer circles it was felt that Makhado’s behaviour was sending the wrong signal to other indigenous groups and they feared a rebellion. Joubert’s compromise was to strengthen the Boer forces’ area by establishing movable steel forts. One of these was established at Muananzhele, on a farm called Boschkopjes. The fort was named after Joubert’s wife, Hendrina. During the Anglo Boer War period and a few years after, this fort was situated at the current Fort Edward and was also called the same. The fort was later moved and today still stands next to the municipal library in Louis Trichardt.

At the same time, however, Makhado had to deal with much more dissent from within his own ranks and some of the mahosi under Makhado asked Joubert for protection against the thovhele. Makhado, always an excellent strategist, realised that he was running out of options if he wanted to avoid a full-scale war. He used several delaying tactics, such as asking Albasini to first demarcate Tshivhase and Mphaphuli’s territories.

Seeing that this article concerns Piet Joubert, we’ll have to jump past the events that occurred between 1887 and 1897. Several very important things happened during this period, including the death of Makhado in 1895, but we may touch on them in other articles. One event that cannot be omitted, is the visit of the Chief Native Commissioner from Matabeleland, Captain HJ Taylor, in 1889. This direct contact between the British and Makhado did not go down well with the Boer forces, who were growing more and more suspicious of the intentions of the British Empire. The subtle interference of the British continued during the reign of Mphephu.

Perhaps to conclude the story of Piet Joubert, we should move to the last battle of the ZAR before the start of the Anglo Boer War, namely the war against Mphephu. This conflict was aptly described by the German missionary, R. Wessmann, when he said it was a short war that “to many Europeans has hitherto been a puzzle …”

When an ageing Piet Joubert was asked to travel north to the Soutpansberg in September 1898 to deal with the matter, he was clearly not enthusiastic about the trip. He left Pretoria on 6 October 1898 and a day later he stopped over in Potgietersrus (Mokopane) where he was joined by 200 burghers from Standerton. In a letter written to his wife, Drienie, he complains about the weather, which varied from sweltering heat to cold, misty rain. On occasions, he writes, it is so cold and misty that one can hardly chase a dog out the door. When Drienie heard that he had also forgotten his warm jacket at home, she packed her bags and a couple of days later she was, as had become customary, at his side on the battlefield.

The war against Mphephu was a strange anomaly and should probably never have happened. Nemudzhivhadi is one of the historians that reckons it was a combination of events and a lack of understanding that caused the war. Mphephu took over the reigns after his father’s death, but he was not regarded by all of his brothers as the rightful heir. Even Sinthumule, who helped him become king a few years earlier, turned against him. The Venda nation was divided and Mphephu did not have the support of important Venda mahosi such as Tshivhase and Mphaphuli.

While Piet Joubert was planning for the battle, he made numerous attempts to try and resolve the matter through discussions. Even though Mphephu, at a later stage, indicated that he wanted to talk, this never materialised. Joubert’s “ultimatums” also did not have any effect. Part of this can be ascribed to a lack of trust, which has its origins some 60 years earlier when Louis Tregardt assisted Ramabulana in 1836 to regain his title. Ramavhoya, who usurped the position of Vhavenda king, was lured by Tregardt’s group out of his stronghold and invited to a meeting. During this meeting, Ramabulana was hiding in a wagon. Ramavhoya and his men were soon overpowered and Ramavhoya was later murdered. Even though Mphephu was a grandson of Ramabulana, the distrust of the white settlers still lingered.

In the period between Joubert’s arrival in the Soutpansberg and the main battle on 16 November 1898, he meticulously moved all his pawns into place. Seven divisions were set up to attack Mphephu’s stronghold from three sides. The forces included a Swazi regiment and the Ermelo, Wakkerstroom, Johannesburg and Krugersdorp commandos, who attacked from an easterly direction. The central division, lead by Joubert, included commandos from Pretoria, Standerton and Heidelberg and also warriors from Sinthumule. From the west, the commandos of Waterberg, Soutpansberg, Middelburg, Carolina and Bethal lined up. The roughly 3 500 Boer fighters were joined by 1 000 Swazis and about 1 000 Shangaan warriors.

Prior to the battle on 16 November, Mphephu’s followers did some rather strange things. These include attacking the laager set up by the burghers on Rietvlei (where the Dutch Reformed Church in Louis Trichardt now stands). This attack was apparently initiated by a drunk Funyufunyu, Mphephu’s main advisor. Mphephu also sent his soldiers to visit the area near the Kranspoort mission station and ordered the people not to pay taxes. In the skirmish that followed, one of the Buys people was killed.

Early on the morning of the battle, the first shots were fired. The commando from Heidelberg stormed a section of Mphephu’s soldiers. The soldiers fled towards Luatame while heavy fog set in over the mountain. When the mist cleared at about 09:00, Joubert gave orders for the cannons to start firing at the royal kraal. When the second shot was fired and a hut caught fire, chaos erupted. This battle lasted less than two hours and at 10:30 the kraal was deserted. Mphephu, along with most of his followers, fled towards the north. The other Boer commandos were involved in some more skirmishes against Phahwe, Malimuwa and Tshitopeni, but the following morning it was all but over.

The search for Mphephu continued for quite some time after that. It eventually transpired that he had fled northwards, where he found refuge in the then Rhodesia. The British South African police met Mphephu and roughly 2 400 of his followers at the river on the border and stopped the Boer forces from pursuing them any further. Mphephu rather naively believed that the British forces would assist him in his fight against the Boer forces, but they (British) conveniently waited for it all to unfold from a safe distance.

On 8 December, the commandant-general made his way back to Pretoria. During a banquet held in his honour, Joubert expressed the wish that a town be established at the foot of the Soutpansberg mountains. On 22 February 1899, the government published a proclamation stating that the new town would be called “Louis Trichardt”.

Joubert was a very religious man and, prior to the battle against Mphephu, he conducted nightly sermons. The night before the battle he made a vow that a church would be built on the terrain where the main laager had been situated. It was eventually left to his wife, Drienie, to make good on this promise, as the Anglo Boer War and his own death denied him this opportunity. Drienie paid over 280 pounds to the Louis Trichardt congregation of the Nederduitse Hervormde of Gereformeerde Kerk. After her death, another thousand pounds were left for this purpose. The first, affordable church building was erected in 1906. The building of the bigger, more majestic church, designed by well-known architect Gerard Moerdijk, was eventually opened in 1926. The first church building served as hall and also a school hostel later on, until a tornado demolished the building in December 1948.

The town thus has a “living monument” to a rather remarkable, albeit often controversial, man. Up to his last battle, he seemed to have held out for as long as he could, believing that the good in men would eventually triumph. This is not always the case and in some cases battles are necessary, and of course, a general to lead.

As far as the Milwaukee Journal’s claim that he was an American soldier is concerned – it is not only unlikely, but practically impossible. Is it a case of mistaken identity, or war propaganda? Perhaps the Milwaukee Journal should publish a retraction, albeit 117 years later.

Sources:

Meintjes, J. 1971. “The Commandant-General. The Life and Times of Petrus Jacobus Joubert of the South African Republic, 1831-1900.” Tafelberg Uitgewers.

Braun, L.F. 2015. “Colonial Survey and Native Landscapes in Rural South Africa, 1850-1913.” Brill.

Nemudzivhadi, M.H. 1998. “The Attempts by Makhado to Revive the Venda Kingdom, 1864-1895.” Potchefstroom University for CHE .

Nemudzivhadi, M.H. 1977. “The Conflict between Mphephu and the South African Republic (1895-1899).” Master’s Thesis - Unisa.

Pretorius, C. 2008. “Vreeslose Drienie. Die Lewe van Hendrina Joubert.” Protea Boekhuis.

-

14. The meeting place of opposing ideologies

22 December 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

13. JC Krogh – The maker of peace?

28 October 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

12. Tracing the origins of the first Indian traders in the Soutpansberg

30 September 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

11. The (secret) story that started with Piet Retief

01 August 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

10. The times were a’changin for a controversial president

20 June 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

-

8. The casualties of war for the souls of the Soutpansberg

18 April 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

7. Bvekenya Barnard - the most famous of Crook’s Corner’s elephant hunters

21 March 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

6. The Englishman who helped shape the course of the country’s laws

29 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl -

5. Piet de Vaal, the stately “baobab” of the Soutpansberg

15 February 2016 By Anton van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT