ADVERTISEMENT:

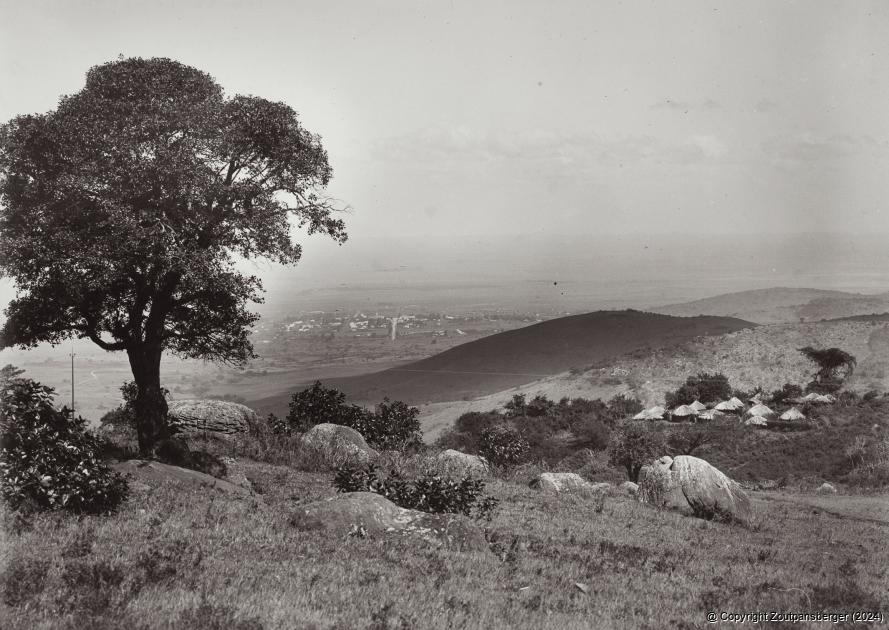

Louis Trichardt as seen from the mountain. Photo from MuseuMAfricA, ref. no. PH2005-56243.

Soutpansberg has lost its lush grasslands

Date: 05 August 2017 By: Anton van Zyl

The Soutpansberg used to have vast stretches of grassland, with the springbok grazing alongside antelope such as the extinct Lichtenstein’s hartebeest. In less than 100 years, the landscape has changed from open stretches of land to trees and bush. The reason for the change can be found in man’s intervention.

A researcher from the University of Venda, Dr Norbert Hahn, recently published a study describing the change in landscape in the Soutpansberg over the past 150 years. Much of his research is based on historical photos and descriptions of the area.

Dr Hahn has been collecting old photographs for more than 25 years. The oldest photos from the Soutpansberg are those of the Swiss photographer, H. Ferdinand Gros. In 1888, Gros took, among others, a photo of “Pisang Kop”, which shows its southern slopes as almost devoid of any tree or shrub growth. These photos, as well as later ones taken by Hugh Exton (1898) and Alfred Duggan-Cronin show (1923), show the rapid transformation from high-rainfall grassland to secondary bush encroachment, alien infestation, silviculture and sub-tropical fruit orchards.

“Through history, no era can account for such an extreme transformation of habitat as that which occurred in the last 180 years when people of European descent arrived in the Soutpansberg region,” writes Dr Hahn. He draws from the 1837 diary of Louis Trigardt, in which the pioneer makes reference to the 15 game species hunted. The three most common species hunted were blue wildebeest, zebra and the Cape eland, but on two occasions springbok were shot in close proximity to the Soutpansberg.

In June 1871, the German explorer, Carl Mauch, passed through the area and he described the foot of the Soutpansberg as almost bare, with tree growth only found towards the slope of the mountain. His observations were echoed by the Swiss missionary, Rev E Creux, when he describes a meeting with Vhavenda king Makhado in 1883. He had to travel up the mountain to Songozwi, and described the grassy area below, noting that the air was filled with the perfume from all sorts of flowers.

Not just the southern slopes of the Soutpansberg have changed over the decades. In August 1917, when T.G. Trevor visited Lake Fundudzi, he recorded the habitat to the east of Sibasa as “…an open down-like plateau, with scattered Protea trees and close-growing grass, which might be taken for a portion of the Transvaal high veld.”

Dr Hahn’s research has indicated that approximately 10% of the Soutpansberg was covered in now-extinct grasslands. “The contributing factors to the demise of these grasslands are complex and usually entail an interaction of various influences,” he states in his research summary. In the study, he discusses some of the factors that may have caused the rapid demise of these grasslands.

One of the reasons the trees and bushes started to encroach, was probably the large-scale culling of the large mammalian herbivores, and more specifically the African elephants. When Schoemansdal town was in its prime (around 1860), João Albasini estimated that between 70 and 80 tons of ivory was hunted annually. When Pater Joaquim de Santa Rita Montanha travelled through Schoemansdal (1855-1856), he remarked that the number of elephants hunted was impossible to estimate. The hunting was also not limited to elephants. Rhinoceroses (both square-lipped and hooked-lipped) were shot for their horns, Transvaal lions were shot for their skins and even Southern ostriches were shot for their feathers.

In 1923, the Venda phala-phala horn was still made from Sable antelope horn. With the demise of the Sable antelope within the area, the Vhavenda had to start using Greater kudu horns to make the phala-phala trumpet.

Keystone herbivores, such as the African elephant, are extremely important in maintaining biodiversity. “The demise of keystone herbivore from the Soutpansberg can in part explain the drastic transformation of the high rainfall grasslands into secondary bush and woodland,” writes Hahn. His research has shown that at least 14 mammalian herbivore species became extinct in the region. “Excessive hunting was most probably the main contributing factor that drove these species to their minimum viable populations, together with rapid change that forced them to extinction,” says Hahn.

Another reason for the bush encroachment was the change in hydrology. Hahn describes how the eucalyptus and pine tree plantations have succeeded in “drying up” the marshy conditions south of the mountains. He explains by mentioning the example of the Louis Trichardt railway station. The railway line was constructed in 1914, but stopped just south of the town at the Ledig siding to avoid the marshy lower town. “In the 1920s it was decided to shift the station to the lower town as the planting of Eucalyptus and Pine trees below Hanglip had dried up the marshes. The new station was opened in October 1928, only eight years after the establishment of plantations,” he writes.

Hahn explains in his thesis that the shallow water table favoured the high-rainfall grassland, but once these were dried up, the secondary woodland tree and shrub species started to take control.

Two other factors that contributed to the change are climate change and the manner in which veld fires were being controlled. Hahn refers to the global rise in CO2 levels, mentioning that this promotes the expansion of woody vegetation into grasslands due to the fertilizing effect of CO2 on tree growth. The South African climate is also following the international trend and is steadily rising.

The effect of veld fires on the environment is often underestimated. “Fire is an important driver towards the maintenance of grasslands in southern Africa, stimulating grass growth and helping with the exclusion of woody species,” writes Hahn. He refers to rainfall models that predict that all areas receiving above 650 mm rain would be covered by forest if fire was suppressed.

The summary of Dr Hahn’s study can be downloaded at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0035919X.2017.1346528?scroll=top&needAccess=true

Viewed: 1803

|

|

Tweet |

-

Vhembe swyg oor gesloer om lekke reg te maak

18 April 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Border fence contractors lose appeal to retain profits

18 April 2024 -

Former Triegie’s acting career taking off

12 April 2024 By Karla van Zyl -

'Temporary fix is safe, but do not touch cables,' says municipality

12 April 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Another R2 million pumped into broken pool

12 April 2024 By Andries van Zyl

Anton van Zyl

Anton van Zyl has been with the Zoutpansberger and Limpopo Mirror since 1990. He graduated from the Rand Afrikaans University (now University of Johannesburg) and obtained a BA Communications degree. He is a founder member of the Association of Independent Publishers.

More photos...

A Swiss missionary and his family on top of the Soutpansberg. Photo from the Cuénod private collection, taken at the turn of the 20th century.

The saltpan to the northwest of the Soutpansberg from which the mountain got its name. Photo taken by H.F. Gros 1888, MuseuMAfricA, ref. no. PH2005-6244A.

View of the foot of Luatama, taken in 1894 or 1898. Photo from the Hugh Exton collection Polokwane.

A hunter at the turn of the century, displaying his spoils. Photo from the Cuénod private collection.

Looking west across the southern slopes of the Soutpansberg, with Hanglip in the background. A 1920 photo from the Giesekke Private collection and 1999 from N. Hahn.

ADVERTISEMENT

-

Park development leaves residents puzzled

22 March 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

Local para-athletes shine at SA Champs

05 April 2024 -

Former Triegie’s acting career taking off

12 April 2024 By Karla van Zyl -

Epic finish for local cycling duo

29 March 2024 By Andries van Zyl -

What next Vhembe!

22 March 2024 By Andries van Zyl

ADVERTISEMENT:

ADVERTISEMENT